August in the Philippines is celebrated officially as “Buwan ng Wikang Pampansa” or “National Language Month” since 1997, or simply, “Buwan ng Wika” – “Language Month”. It is marked every year by promoting appreciation of the country’s National Language, “Filipino”, by strongly encouraging its use in schools for the entire month.

During my time in the Philippine elementary and high school education system, “strongly encouraged” meant, ironically, forcing students to speak a language not their own or face a penalty. After all, what the Tagalog-based government refers to as “Filipino” is really just Tagalog, the native language of the Tagalogs, located in the Tagalog region. A language NOT natively spoken in over two-thirds of the country.

I’m told there have been great strides since then in educating our own education officials on language appreciation by not limiting the idea of the “Philippine language” to just one (technically two, as English is also a Philippine National Language1, though you’d never know it during Buwan ng Wika).

Although Filipino is still the National Language last I checked, schools have since stopped docking students’ grades or making them pay 25 cents for every non-Tagalog word they utter during Buwan ng Wika. In recent years, Buwan ng Wika has even included actual appreciation of other local languages in many government- and privately-run schools. That’s a definite turnaround from being penalized during my time for speaking my own native Bisaya. Baby steps, but in the right direction, I suppose.

While there are now growing strides in correcting the notion that a Philippine language is only one specific language, there is also one huge missed opportunity in the 77 years (125 years if you subscribe to the idea that we’ve been “independent” since 1898) this country has had since it was able to reassert its own identity as a nation to unite its people under a truly singular language, one that has been officially neglected despite being truly our own—the written language of the Philippines: Baybayin.

To stress a point, there’s a 99.9% chance (allowing for 0.1% margin for error) you’re reading this article in English, using the Latin alphabet. You may not immediately notice, but neither English nor Latin are native to the Philippines.

“Baybayin” means “to write” or “to spell out” in Tagalog. Another completely valid name for this written language or script is “Badlit”, which means “to etch”, “to mark”, or simply, “to write” in Bisaya. In the dozens of languages spoken in the Philippines, there are almost as many ways to formally call this way of writing, but they all refer to the same, single-written language–the same script used across multiple languages.

Unlike Tagalog which is a minority spoken language, Baybayin was used by almost all the native peoples of this archipelago for hundreds of years prior to the 16th century, regardless of their spoken language. The usage rules of Baybayin mean that practically any spoken language can be used with it.

Before Spain claimed the archipelago as its territory and imposed its own set of oral and written languages, Baybayin was recorded as being in use by native speakers of the Visayan Language Family (Badlit) in the Visayas and Mindanao, as well as speakers of Ilocano (Kur-itan), Pangasinense (Kuritan), Sambali (Kulitan) Kapampangan (Kulitan), Tagalog (Baybayin), Hiligaynon (Baybayin), Bicolano (Basahan), and Palawano (Tagbanwa), with the Mangyan (Hanunó’o, Buhud) in Mindoro having multiple derivatives on the same island, depending which tribe you belonged.

These were all based on the same mother script with some degree of variation, although a Baybayin-proficient reader trying to read Buhid may need to sit down and clear their schedule for the day.

For the sake of brevity, the rest of this article will refer to this Philippine native script as “Baybayin”, as this seems to be the most commonly used name (although any of the others above are just as valid).

At one point, Baybayin was erroneously referred to as “Alibata” due to an early 20th-century Filipino scholar’s assumption that the script was based on Arabic script and thus named it after the Arabic language’s first three characters: alif, bāʾ/baa, and tāʾ/taa. Baybain is, in fact, an evolution of the Brahmic script–the written language of South Asia.

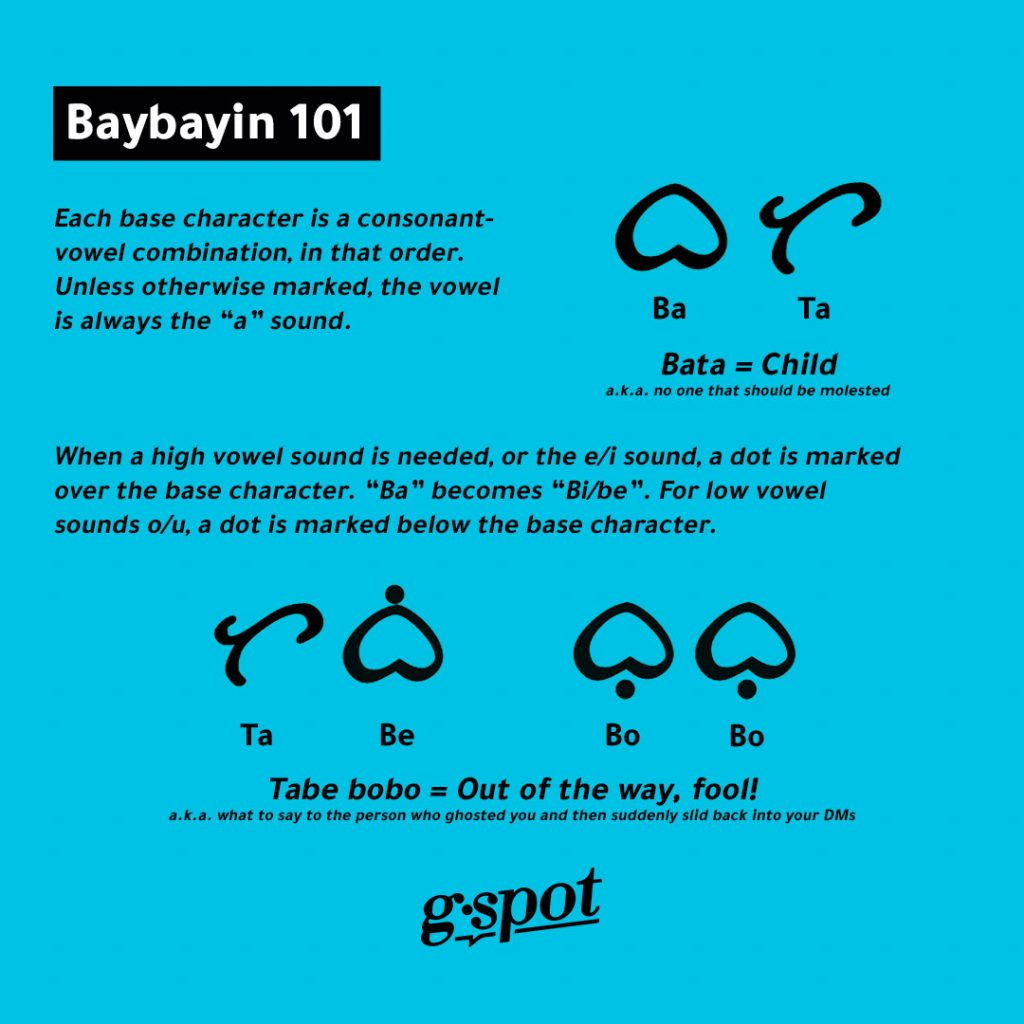

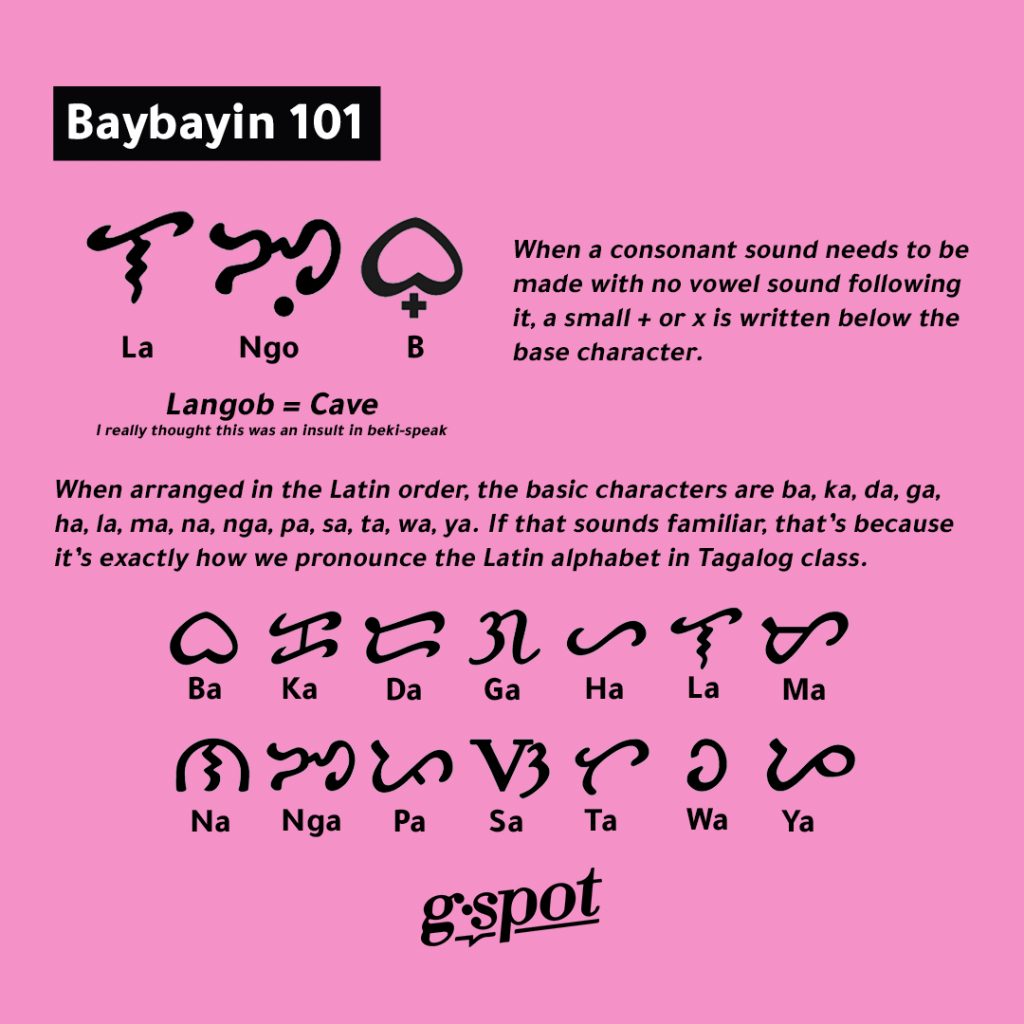

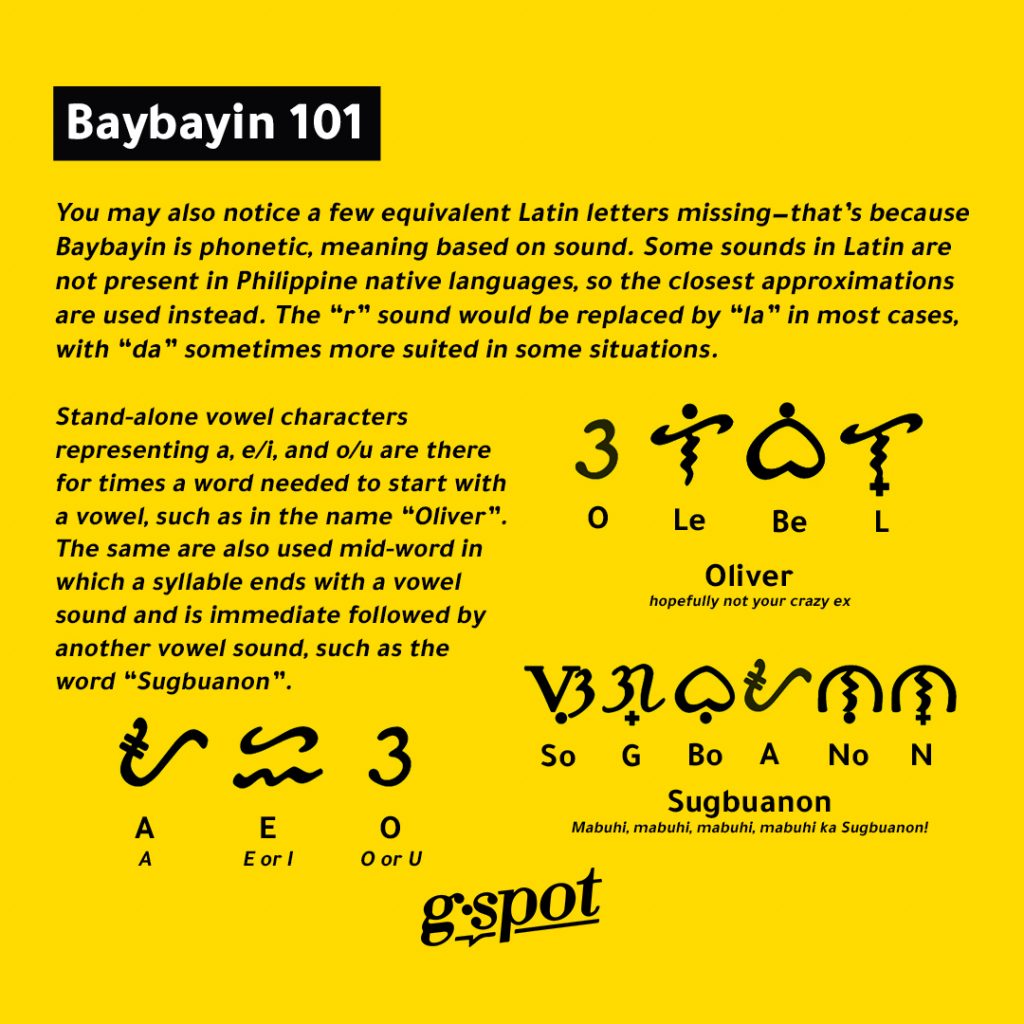

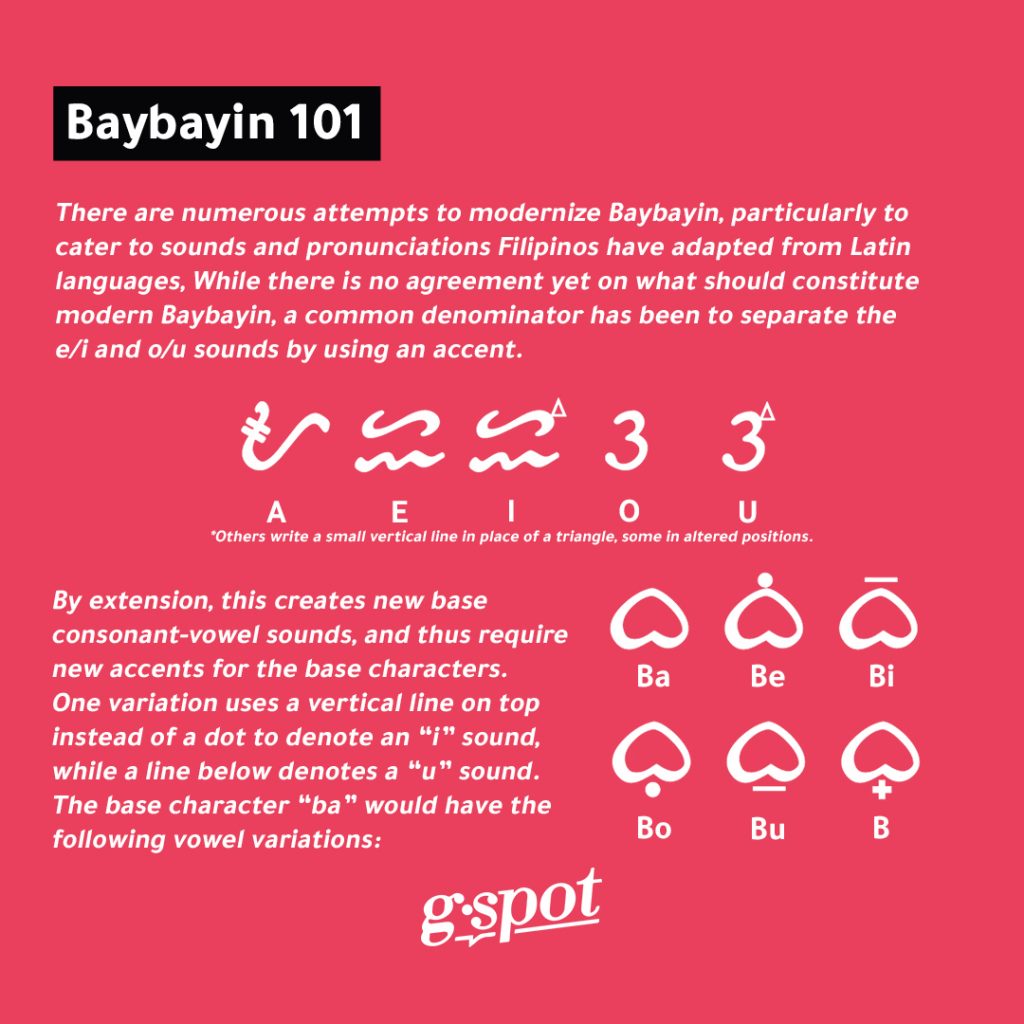

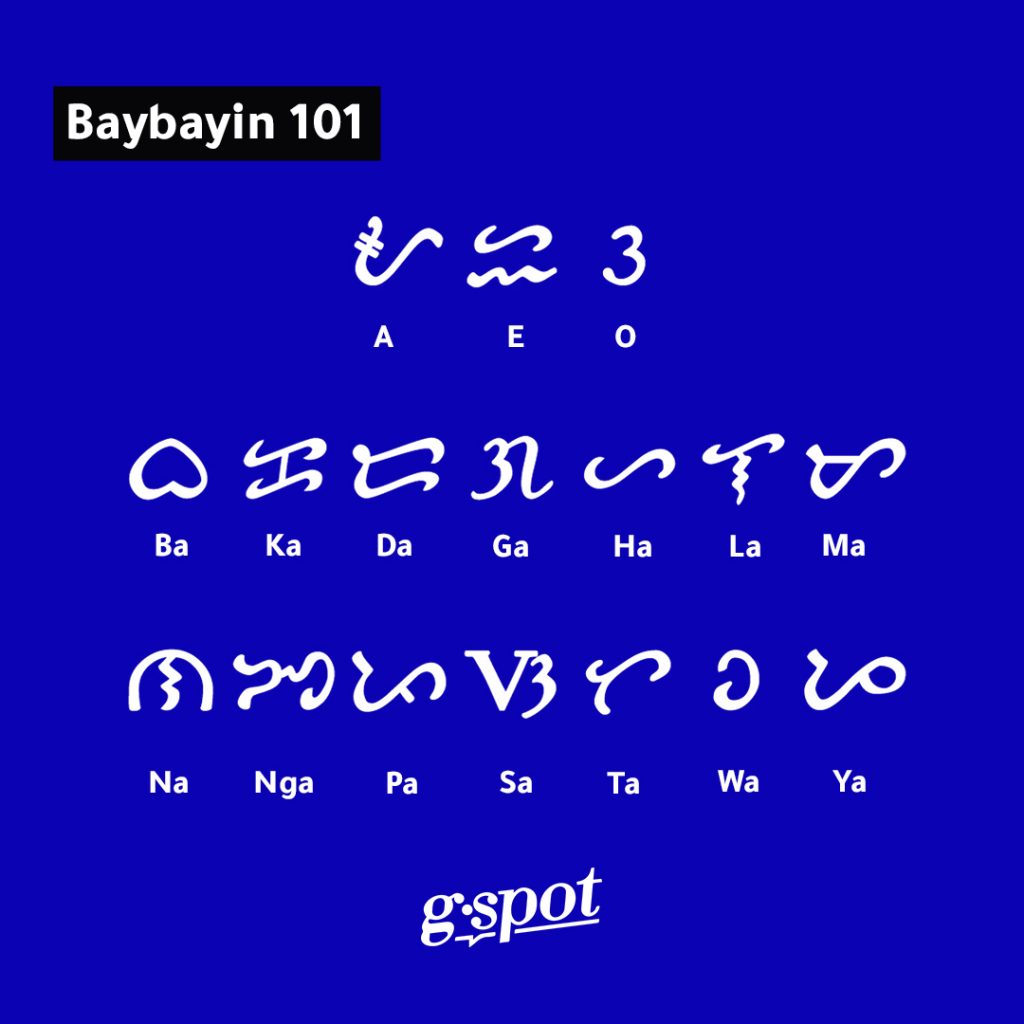

The reason Baybayin became so widespread is because its usage evolved from its parent script to become simple and consistent, and thus easy to learn. Any learning curve is in memorizing its base characters, which, having no similarity to the Latin alphabet we’re taught in schools, requires one to familiarize oneself with completely new shapes.

One of the main advantages of Baybayin is its syllabic and phonetic nature, or alphasyllabary. Every character is a syllable, and every syllable is based on its corresponding spoken sound. Regional variations of the script tend to have their own minor variations on this rule, but scholars in the early 20th century created a standardized form that caters to all variations.

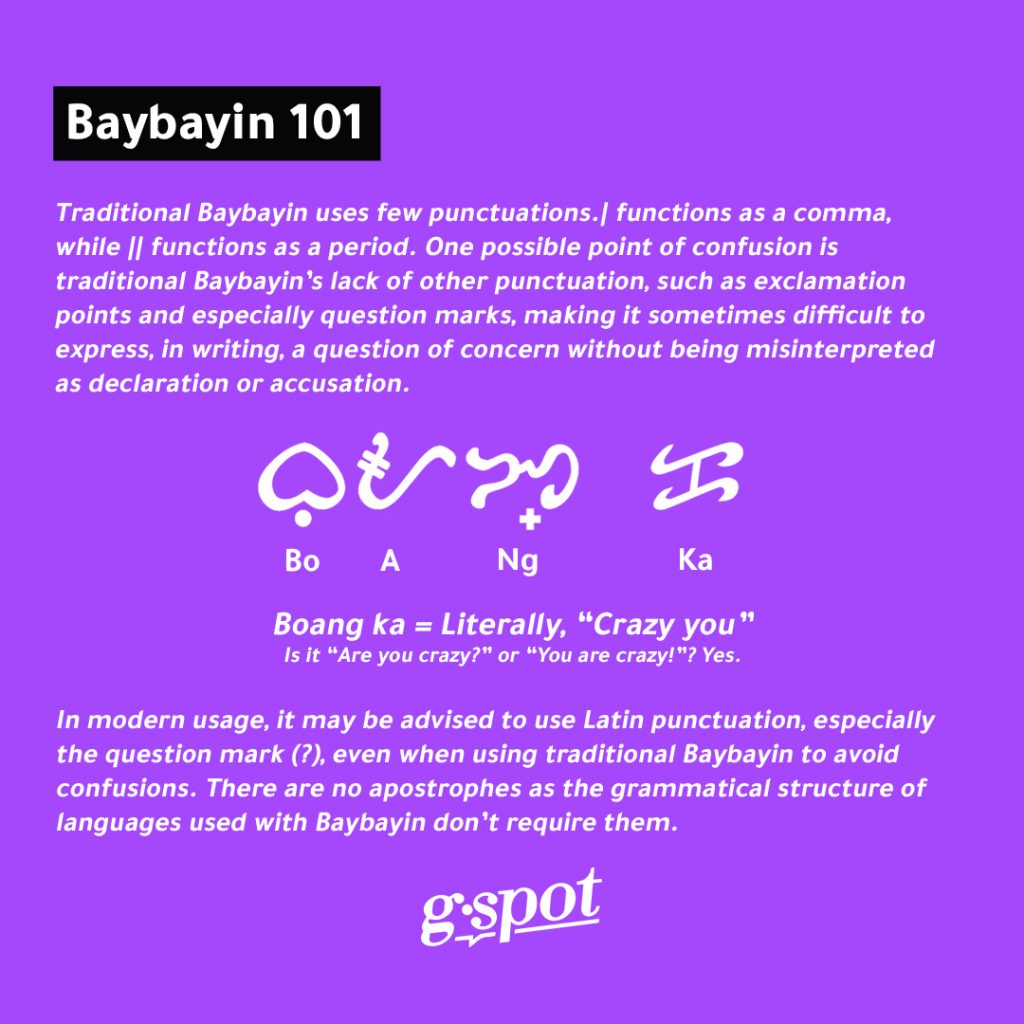

If there is one thing that Baybayin lacks, even with modern standardization, it is punctuation. While there are equivalents of commas and periods to denote sentence pauses and full stops, Baybayin, even with modern standardization, does not have the equivalent of an exclamation point and, more importantly, a question mark. This sometimes makes certain written sentences sound like declarations even though they’re meant to be questions. In modern times, this can be alleviated by adapting the Latin equivalent punctuations.

Easy to learn, crossing multiple Philippine cultures, and a script truly our own, it is unfortunate that Baybayin has never had official recognition of any sort since the Philippines became a nation.

Thanks to Filipino language scholars, however, the script has been kept alive, and interest in it is growing. Local language professors throughout the decades tend to keep their own copy and teach it to anyone who wishes to learn.

Thanks to the advent of the Internet, information on it is now widely available online, with an increasing number of Filipinos, particularly younger generations, taking an interest in it and learning it by themselves. Many private organizations now also offer classes on its use, although, from the possibly outdated information I have, I’m still not aware of any schools that offer to teach Baybayin formally, even as an elective. (PLEASE correct me if this is no longer true, I’d truly like to know).

The use of Baybayin is now also slowly creeping into mainstream culture, purely by the efforts of the Filipino people themselves. A growing number of native-oriented establishments and products are starting to use the script as an alternate way to write their branding. Others even offer product customization to have Baybayin print etched, burned, or inked into a custom product.

There is even a bag brand with an extensive line of products all centered around the Baybayin script that is aggressively marketing their products these days, although, upon closer observation and reading, the Baybayin on their bags are almost always centered around the Tagalog subculture. I look forward to buying their products when they embrace the broader Filipino culture.

Even government offices, especially those dealing with culture, arts, and entertainment, have slowly adapted Baybayin into their signages and even official logos, some even including Baybayin translations on their building, department, or office name signages. The National Museum is at the forefront of this effort, with many other government agencies following suit.

Even official Philippine IDs have it: Look at your Philippine passport; there is Baybayin script on the page opposite your personal information. It says, “Ang katuwidan ay madakila sa isang bayan”, an archaic Tagalog way of saying “Righteousness exalts a nation,” a quote lifted from the Bible’s book of Proverbs, 14:34. Yet this nation has never officially recognized the one written language that is rightfully, truly, its own.

Thankfully, the Filipino people themselves are at the forefront of Baybayin revival. Even though I was willing to write this article entirely in Bisaya Baybayin to prove a point, the vast majority of you reading this article probably wouldn’t recognize the script, much less read it. Also, there is a great shortage of printable Baybayin fonts supported by publishing software.

And despite being an avid supporter of our native script, alas, I personally rate myself a neophyte when it comes to writing and reading Baybayin, and would thus take me ten times longer to write this piece.

Which highlights the point of this article: We DO have a native Filipino script. We as a people and a nation are obviously trying to get back in touch with our cultural roots. There are many willing to learn it. Why aren’t we using Baybayin as an official script yet and teaching it to our youth in our schools?

Here’s a callout to our culture and education officials: give Baybayin its due. Recognize it as the National Written Language or National Script. And offer it at least as an elective for those who wish to formally learn the one language that has tied together our peoples since this nation was not yet even a nation.

1 According to the 1987 Philippine Constitution, Article XIV, Section 7